To track the movement of the coronavirus, which is evolving at an almost daily pace, some countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, have resorted to wastewater surveillance and analysing samples to monitor the presence of the virus in an area even before any infection arises.

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized the need for tests that yield rapid and accurate results for individuals and countries. Two main tests have emerged: the "polymerase chain reaction", the molecular test that detects the genetic material of the virus, and the second antigen test that investigates the presence of certain proteins on the surface of the virus.

More than 3 years have passed since the discovery of the first cases in the Chinese city of Wuhan, during which several treatments, vaccines and diagnostic tools appeared, and countries are still seeking to recover from the economic and social effects of the lockdown.

The United States can no longer bear the consequences of another lockdown, after home tests have become more than those conducted in laboratories, and official statistics have reached an unprecedented level accompanied by a general atmosphere of anxiety and unreliability, while the virus is developing itself to show more powerful mutants; longer life, and faster spread. As the symptoms of these variants are fewer, the ability of the health authorities to track the virus will diminish, which prompted them to search for other means to monitor its movement and spread.

Many technologically advanced countries resorted to the study of pathogens from a chemical source. While medical teams on the ground take samples from patients' noses and mouths, other teams are working to collect samples from another underground source, from sewage.

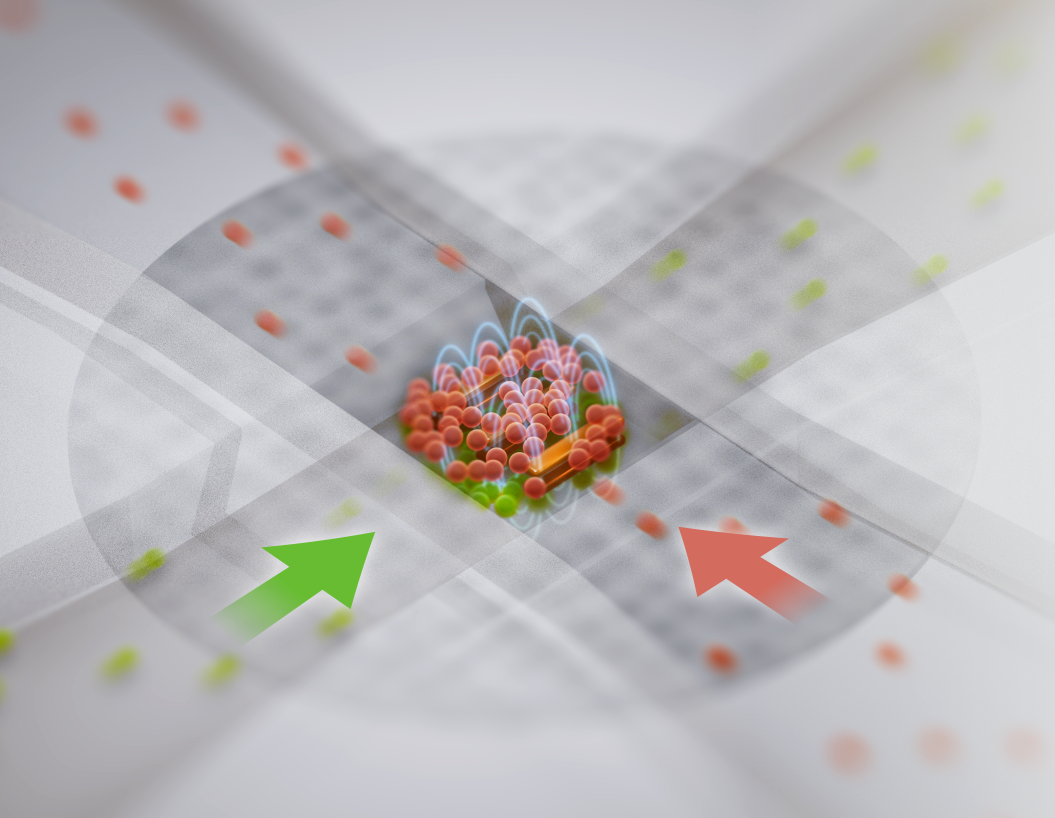

It is a fact that the coronavirus is transmitted through respiratory secretions, but researchers estimate that half of these secretions find their way into the sewage system. There, the genetic material of COVID-19 or its variants can be identified in a non-infectious state.

A sewage sample is taken by laboratory staff to detect the genomic sequence of the genetic material, through which they can determine the points of spread of the virus or its decline, or the emergence of new variants, during the 15 days preceding the sampling. If a site does not detect the coronavirus after performing at least one test during that 15-day period, it will be logged as “non-detects”. If no samples were collected during the 15-day period, it will be labelled as “no recent data”.

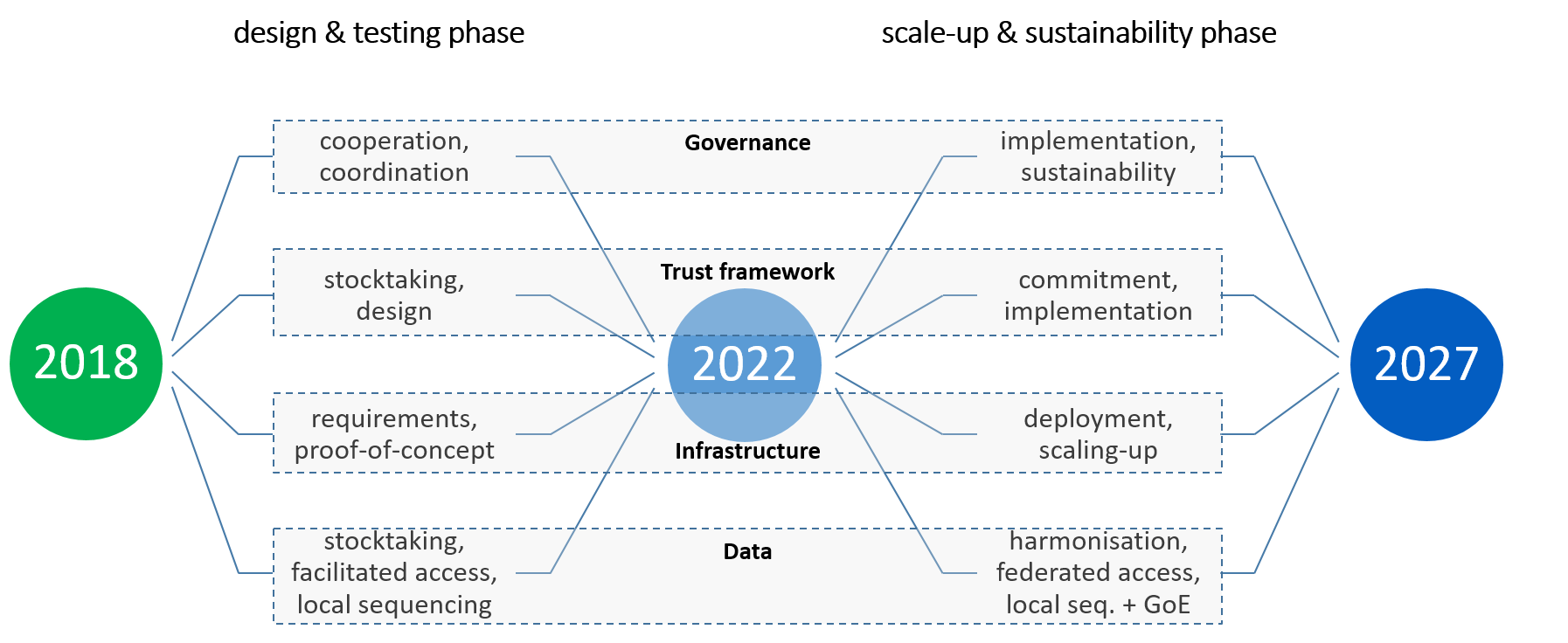

Based on this and approximately 6 months after the first cases appeared, the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) launched the National Wastewater Surveillance System, with funds that ensure that it will continue to publish data on 400 different sites until 2025, while many government entities concerned with public health and the environment have established their own dashboards and databases with data collected by the system.

Gradually, this method is gaining increasing popularity in countries such as Switzerland and Italy, as well as the United Kingdom, which embraced the first experience at Bangor University, and launched The Environmental Monitoring for Health Protection (EMHP) Programme, where a team of experts applied this mechanism in some major cities such as Manchester and Liverpool. After tracking virus levels, they drew up a rough map of local cases, followed by a national wastewater monitoring programme, through which, for example, the health status of 40 million people in England alone is monitored.

However, this method may not be generalizable as some areas may not have the necessary infrastructure or organized sewage networks to conduct this type of test. Until these networks are ready in every US state or British town, the data will remain limited.

Although 38% of US local public health agencies have implemented this method, only 21% plan to continue using it, which is barely more than half. The scientific methodology, from a specialized point of view, still needs to be developed, and the data may not always meet the standards of accuracy and reliability. After all, the sewage network is the final destination for many types of wastewater, such as rainwater, animal waste, and others. All of this may affect the accuracy of the samples.

Some states have faced their own challenges. In Philadelphia, for example, data collection, dissemination and updating processes take a long time, because the Philadelphia Department of Public Health has to send its samples to the laboratories of Michigan State University and wait for the results for days or even weeks. This simply defeats the main goal of the methodology, which is to quickly predict the movements of the virus and intervene in a timely manner. If all the necessary requirements are in place, these tests can detect cases days before symptoms appear. They may also detect variants before the first infections appear, which would facilitate taking the necessary precautions and decisions about resource allocation, lockdowns, testing and vaccinations. Wastewater testing is safe, low cost, and able to cover a wide segment of the population without any privacy violation. It is a suitable option for tracking emerging changes and accelerating response to protect public health.

References:

https://edition.cnn.com/2022/05/18/health/covid-wastewater-data-not-understood/index.html

https://www.theverge.com/2022/2/4/22917887/cdc-covid-19-wastewater-tracking-pandemic