As cities around the world grapple with plummeting air quality, Serbia is experimenting with a biotechnological fix that’s as surprising as it is simple. Called Liquid Trees, this urban innovation fuses environmental science with scalable tech—offering a new model for air purification that could reshape how cities manage pollution and green infrastructure.

In today’s concrete and steel jungles—where human ambition rises skyward—a silent threat lingers in the air: pollution. Born from the same engines that drive urban growth and industrial progress, it is now turning cities, the very centers of culture and innovation, into battlegrounds against an invisible adversary.

Often dubbed the “silent killer,” air pollution claims more lives each year than many of the world’s deadliest diseases combined. It poisons the air, taints water supplies, and seeps into food systems—permeating nearly every aspect of daily life.

In Belgrade, Serbia’s capital, the problem is particularly acute. The city relies heavily on coal-powered energy and is home to two major power plants. In 2019, it was listed among Europe’s most polluted cities by the Health and Environment Alliance. A year later, Serbia ranked 28th globally for fine particulate matter (PM2.5) concentration—about 4.9 times higher than what the World Health Organization recommends.

To put that in perspective: Serbia topped all of Europe in per-capita pollution-related deaths in 2019. And with over half the population living in urban areas—and rapid urban expansion showing no signs of slowing—pollution and greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, underscoring a growing environmental crisis.

Faced with this reality, researchers at the University of Belgrade’s Institute for Multidisciplinary Research, in collaboration with the Stari Grad municipality, UNDP Serbia, and the Ministry of Environmental Protection, launched a first-of-its-kind solution: Liquid Trees.

The project is grounded in an elegant idea: sometimes, the solution to massive problems lies in small, even microscopic, innovations. In this case, the answer came from microalgae, organisms with the ability to absorb carbon dioxide and produce oxygen via photosynthesis—at a rate up to 10 to 50 times more efficient than traditional trees.

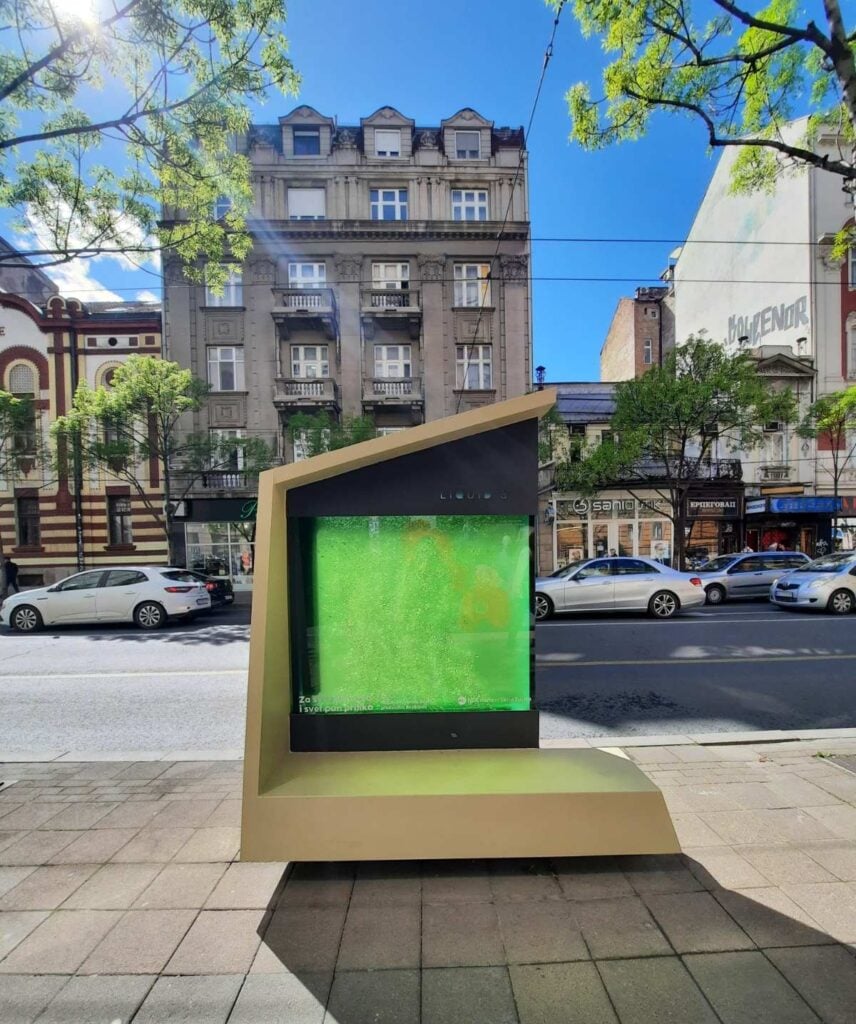

Supported by government funding, the team designed a multi-functional photobioreactor, a transparent tank holding 600 liters of freshwater and oxygen-producing microalgae. These algae can thrive not only in freshwater but also in tap water and across a range of temperatures, making them well-suited for urban deployment.

The system was engineered for low maintenance: algae biomass is harvested every six weeks for use as organic fertilizer, while fresh water and nutrients are added to sustain the population and prolong the reactor’s operational life.

Several of these units have already been installed across Belgrade. Designed for maximum spatial efficiency and 24/7 autonomous operation, they often take the form of public benches—equipped with solar panels, USB charging ports, and LED lighting, turning previously unused sidewalk space into multifunctional, eco-friendly infrastructure.

But despite its promise, Liquid Trees faces critical challenges.

The first is technological scalability: ensuring that the system performs equally well across different climates and pollution conditions. This has required extensive testing and environmental calibration to avoid performance drops in varied urban settings.

The second is public acceptance. People tend to be skeptical of non-traditional solutions—especially when a glowing bench filled with algae is proposed as a substitute for trees. Overcoming public resistance and reshaping perceptions of what “green space” can look like has been essential to the project’s rollout.

Finally, there’s the matter of durability and upkeep. Long-term viability—especially in regions with extreme weather or heavy pollution—requires a system that can withstand harsh environments. Here, the inherent resilience of algae and the system’s minimal maintenance needs have proven key to sustainability.

Despite these obstacles, Liquid Trees is already delivering measurable environmental and social impact. It offers a practical solution to mitigate urban air pollution, sequester carbon, and boost local biodiversity—all while generating natural fertilizer.

Perhaps most importantly, it provides clean air in high-density areas without occupying valuable urban land. Its compact design and dual function as public furniture make it a compelling candidate for integration into smart city infrastructure—a low-footprint, high-impact tool for environmental health.

By combining form, function, and ecological performance, Liquid Trees might not replace forests, but it could redefine how cities breathe.

References